Thy will be done: The miracle of Ryan James

Father, if thou are willing, remove this cup from me; nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done.

~ Luke 22:42

Be careful what you pray for

As I entered the hospital delivery room in Fairfax, Virginia to deliver my fourth child, I said,

“I’m offering all my suffering in this delivery for the conversion of a relative.”

I knew that in some mysterious way God takes our suffering and uses it for good.

My obstetrician, Dr. John Bruchalski, responded,

“Be careful what you pray for.”

I said,

“Well, I didn’t ask God for extra suffering, just the regular amount.”

The doctor later told me that he had a premonition that something catastrophic was going to happen during the delivery.

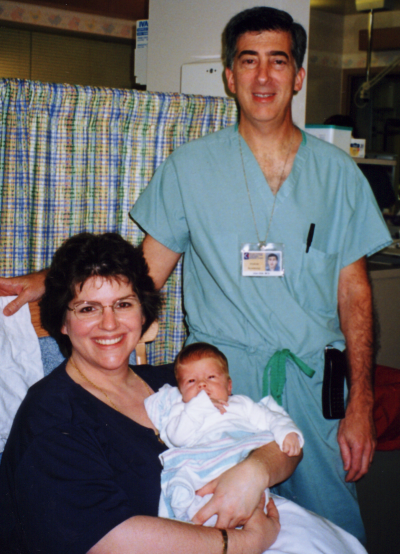

Ryan James was delivered by scheduled caesarean section in September 2002.

Because of my deteriorating health due to diabetes and a heart condition, it became necessary to deliver the baby a few weeks early.

Although he was pink and crying vigorously at birth, within one hour, he was gasping for breath. Although he was not premature at 37 weeks and weighed a reasonable 7 pounds, 7 ounces, his lungs were as underdeveloped as those of a 30-week premature baby, most likely because I am diabetic.

Dr. Alan Silk, neonatologist at Fair Oaks Hospital, put Ryan on oxygen—first delivered through a clear plastic helmet called an oxy-hood, later through nasal tubes.

Ryan also received the first of three doses of surfactant. Surfactant is a detergent-like substance that helps inflate the air sacs of a newborn baby’s lungs; premature babies often lack surfactant, since it is manufactured only in the last weeks of pregnancy.

Ryan’s white blood cell count was low, which indicated an infection. That evening, Dr. Silk started Ryan on precautionary antibiotics (ampicillin and genomycin) to wipe out a possible systemic infection in his blood (this condition is called sepsis). Before starting antibiotics, Dr. Silk took a blood sample to culture for bacteria. Later, we discovered the culture was negative, so the infection was probably caused by a virus, which can’t be cured by antibiotics.

Because of Ryan’s unstable condition and my surgery, I had only seen Ryan for a few minutes just after he was born. Still confined to my hospital bed, I called the nursery for an update at 5:30 a.m. the next morning. I discovered that Ryan had been put on a ventilator (breathing machine) at 100% oxygen.

When I realized how sick my baby was, I knew I must call a priest to baptize him.

I watched the clock until about 7 a.m., then I paged Father Marcus Pollard of St. Veronica parish, whose parish includes Fair Oaks Hospital. Father Pollard told me he would rush over to baptize the baby whenever I needed him.

When my husband Tom arrived at the hospital, I struggled out of bed with the epidural needle still in my back and took a shower. I needed to see my baby.

Just before noon, Tom and I went to see Ryan. How terribly sick and pale he looked, lying limply in a crib while a ventilator pumped air into his tiny chest. His eyelids fluttered a few times, but he was too weak to open his eyes.

Father Pollard arrived around noon to baptize him. As he poured water on Ryan’s knee, he said, “I baptize you, Ryan James Elam, in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

As soon as the priest spoke these words, my heart was eased, knowing that I had done everything I could for Ryan.

Now if he died, I took comfort in knowing that his soul would fly straight to heaven.

(He was later conditionally baptized on the head in the usual way, in case the hospital baptism was invalid.)

A prayer request

Dr. Silk decided to move Ryan to Fairfax Hospital, where a special chemical called nitric oxide would be added to the oxygen already delivered by the ventilator. Nitric oxide helps the lungs work better than oxygen alone.

By 4 p.m., it was clear that Ryan was near death. The blood vessels from his heart to his lungs collapsed, so his blood was getting very little oxygen; this condition is called PPHN or Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of the Newborn.

I kept saying, “I’m so glad he’s baptized.”

As the doctors and nurses tried to stabilize Ryan for his ambulance ride, his oxygen level dipped to 25 (normal is 80 to 100). He turned a deathly grey; I knew my baby was dying.

I told Dr. Marie Anderson, my other obstetrician, that I had offered my suffering for the conversion of a relative. Then I added, “My relative must be a hard case, because I sure am suffering.” Later, I was told that this relative was praying for Ryan’s recovery.

I watched the doctors and nurses try to save my baby’s life, crying into a towel, “My baby’s dying, my baby’s dying.”

A nurse led me into the hall, where I sat down with my husband to pray and cry. I asked the Blessed Virgin Mary to intercede for Ryan before God; no one knew my agony better than Mary, who had watched her own son Jesus die.

After we prayed, I put a prayer card with a picture of Mary in Ryan’s ambulance transport crib.

I sat and thought about what I could do for Ryan. I knew that God sometimes allows another to take on a person’s suffering. Then I whispered to God, “Let my baby live and give his suffering to me. But not my will but Thy will be done.”

I was afraid what might happen to me after this. But I said to myself, “Who loves this baby more than I? Who else would offer to suffer for him?”

The next day, I began suffering suffocating asthma-like symptoms, even though I don’t have asthma. I was told that my symptoms were probably caused by iron-deficient anemia due to blood loss during delivery. It is no coincidence, however, that I began to have trouble breathing only after I offered to take on Ryan’s suffering.

While we were praying, Ryan hovered at the edge of death. Dr. Silk exhausted all medical options available to stabilize him, but nothing helped.

Then it occurred to the doctor that Ryan might have undiagnosed heart disease; there was no way to find out until he was moved to Fairfax Hospital. As a precaution, Dr. Silk gave him a shot of prostaglandin, a medicine used to treat cyanotic heart disease. This medicine temporarily opened the blood vessels to Ryan’s lungs and stabilized him enough to be moved. Dr. Silk’s inspired action, and God’s providence, kept Ryan alive on the ambulance ride to Fairfax Hospital.

At Fairfax Hospital, Ryan was immediately put on a ventilator with nitric oxide and oxygen, which quickly brought his oxygen level into the normal range. An echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) showed that Ryan’s heart was strong and healthy. The problem was just in his lungs.

By the time we checked on Ryan and talked to Dr. Beck and Dr. Lazarte, Fairfax Hospital neonatologists, it was nearly 10 p.m. Wednesday night. The hospital staff arranged for us to stay at the Ronald McDonald House on the grounds of Fairfax Hospital.

Ronald McDonald Houses are available nationwide for families to stay in while their critically ill children undergo treatment at nearby hospitals. What a blessing to be welcomed by the staff and offered a comfortable room for only $10 per night.

At 5:30 a.m. Thursday morning, the Ronald McDonald House manager knocked on our bedroom door. The hospital staff had phoned. Ryan had become unstable even at the maximum nitric oxide dose and 100% oxygen. The only hope left for Ryan was a rare treatment called ECMO. Only two hospitals in the Washington area had ECMO machines.

Tom rushed to the hospital to sign papers allowing Ryan to be moved to Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., where an ECMO machine was available.

Ryan was supposed to be transported by helicopter. After several anxious hours of waiting for a helicopter to arrive from Children’s, we were told the nitric oxide machine would not fit on the helicopter, so an ambulance was sent instead.

Ryan arrived at Children’s National Medical Center at two days old.

When we arrived at the hospital nursery, we scrubbed up to the elbows and went in to see Ryan. It was a shock to see all the tubes and wires connected to him: an intravenous line into his belly button to measure oxygen and carbon dioxide levels; electrodes on his chest to measure heart rate; a catheter in his arm to deliver water, vitamins, and medicine; another catheter to drain urine; a clear tube in his lungs to suction mucus; a white ventilator tube to send air into his lungs; a blue ventilator tube to let air out of his lungs; and a feeding tube (called a gavage tube) from his mouth to his stomach.

He was receiving the same treatment as at Fairfax Hospital—a ventilator delivering 100% oxygen and nitric oxide, three blood pressure medicines (epinephrine, dobutamine, and dopamine) to keep his blood pressure from dropping, and a paralytic drug called pavulon, which kept him paralyzed so he wouldn’t breathe against the ventilator. The only difference was that the ECMO machine was now available if needed.

The hospital staff arranged for us to stay at the Ronald McDonald House in Washington, D.C. When we arrived, I rested in the rocking chair in the lobby while Tom checked in. I was weary and aching from abdominal surgery only two days before.

Celia, the manager on duty, presented us with a baby quilt, a photo album, and a polar bear toy for Ryan. These may be the only gifts my baby will ever have, I thought. I knew nothing about the ECMO treatment, except that if it didn’t work, Ryan would die.

The Lord giveth; the Lord taketh away

I believe the Blessed Virgin Mary heard our request for her intercession and sent us three signs. When we first visited Ryan at Children’s, I was sad to discover the Mary prayer card placed in Ryan’s transport crib had been lost during the move from Fairfax Hospital.

That evening, as we returned to our room at the Ronald McDonald House, we met a Catholic woman. When she realized we were Catholic also, she said, “Wait, I have something for you.”

She disappeared into her room and returned a moment later with a large picture of the Blessed Virgin Mary. She said, “When I was at the Basilica yesterday, I accidentally bought two pictures of Mary. Now I know why; I’m supposed to give this one to you.” And she did; that was the first sign.

The second sign came a week later, when we received a letter from Fairfax Hospital. Inside was the lost prayer card and a letter from a woman who said she was returning the prayer card to us and signed her name only as “Mary.”

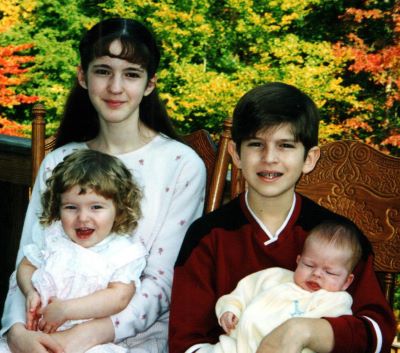

On Sunday morning, Tom picked up our three older children to attend church. Becca, almost 12, had been staying with friends during the week so she could attend Seton Catholic School in Manassas. Kevin, 10, and Teresa, 19 months, had been staying with my sister Pamela and her family in Maryland.

We attended Mass at the Franciscan Monastery next door to the Ronald McDonald House. During the service, I wondered sadly if Ryan would die before the other children ever saw him.

Several nights I had dreamed of Ryan dressed in a white baptismal gown, lying in a tiny coffin.

From the Franciscan gift shop, I carefully chose four prayer cards—Jesus, Mary, Joseph, and James the apostle (Ryan’s patron saint)—and a blue rosary to bring him as gifts. I cried to think I might be burying these gifts with him.

Around noon, I began to suffer from the worst migraine headache I have ever experienced.

When we arrived at the hospital Sunday afternoon, we were distressed to discover that the hospital staff had been trying to reach us since noon without success. Ryan’s condition was deteriorating; his oxygen level had been dipping from the 90’s into the 70’s all afternoon. Brain damage can occur below this level.

I believe my headache was spiritually related to Ryan’s suffering that day.

Ryan’s doctor, Dr. Mary Revenis, had decided to put Ryan on the ECMO machine. She explained that two plastic tubes would be inserted into one of Ryan’s jugular veins and threaded down to his heart. The ECMO machine, which is a heart-lung bypass machine, would take blood from his body, oxygenate it, and then pump it back into him. The machine does most of the work of the lungs and heart, allowing these organs to rest and heal for several weeks, if necessary.

Because complications such as blood clots can be fatal, ECMO is reserved for patients who will die without it. Even so, the doctor assured us that 90% of ECMO babies survive.

Since it took several hours to set up the ECMO machine, Becca and Kevin were allowed to see Ryan for a few minutes.

As the nurses began to set up for the ECMO operation, I quickly taped the rosary and four prayer cards on Ryan’s crib.

Whether he lived or died, I accepted God’s will with the prayer, “The Lord giveth, the Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.”

Only much later did I notice the date of that Sunday on which Ryan’s life-saving operation took place: September 8th, the birthday of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This was the third sign.

Coming home at last

During the four days that the ECMO machine oxygenated Ryan’s blood and pumped it back into his body, his lungs were able to rest and heal somewhat.

It was shocking when we first saw Ryan―a little baby with his blood pumping through tubes that ran from his jugular vein to the ECMO machine. A nurse noticed Tom looking pale and quickly offered him a seat to keep him from fainting.

A Nigerian missionary priest, Father Dominic Eshi Kena, visited Ryan and prayed fervently over him three times. I told him how I offered to take on Ryan’s suffering. He said, “I always offer to take on the suffering of the patients I visit. When other priests ask me why, I tell them it works. I’ve never had it fail.”

I told him that the Blessed Virgin Mary had interceded to help Ryan and described the signs she had sent us. I said, “People may not believe me, but I know she helped Ryan.”

Father Dominic urged me to share Ryan’s miraculous story with everyone I met.

Ryan was taken off the ECMO machine when he was nine days old. My asthma-like symptoms started the day after I offered to take on Ryan’s suffering; they stopped the day after Ryan came off the ECMO machine.

He was weaned from the ventilator two days later, but continued to receive oxygen through nasal tubes for another week.

On day 17, Ryan was moved back to Fair Oaks Hospital at our request. This transfer allowed me to leave the Ronald McDonald House after three weeks and come home.

For the next week, I visited Ryan every day in the hospital as he made steady progress: first, he was weaned off extra oxygen, then he learned to bottle-feed, finally to nurse.

Even though he was still breathing twice as fast as normal at 60 breaths per minute and his chest retracted (sank in) when he breathed, the doctors expected full recovery of his lungs by age two.

Ryan came home on September 28, after spending nearly a month in the hospital.

I give thanks to all the dedicated doctors and nurses who were God’s instruments in saving Ryan’s life.

I give thanks to the Blessed Virgin Mary for interceding for Ryan.

Most of all, I give thanks to God for giving our precious baby back to us.

God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pain. Pain is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world.

~ C. S. Lewis

Postscript: Ryan turned 18 years old in September 2020. His lungs fully recovered and he did not suffer any brain damage or developmental delays. He is now a freshman in college after receiving a full academic scholarship as a National Merit Scholar.

Written: December 2002

Revised: January 2021